Investigation

Medicine dealers: Europe’s secret drug negotiations

Patients suffering from cancer or other serious diseases rarely realise that their fate can depend on secret price deals struck between state officials and pharma executives, according to research by Investigative Europe.

“The negotiation is totally secret. Everything moves around in sealed envelopes, changing hands with signatures,” one negotiator from a mid-sized EU country reveals. “We don't even put it in our electronic systems because we don't want the contractor who maintains our systems to have access.”

States think they make big savings from these secret deals, but in reality, they are pitted against each other, unaware of what others really pay.

Despite the discounts, governments are often charged extortionate fees for life-saving medicines – or they are unable to access them altogether, an eight-month investigation by Investigate Europe and its partners has found.

Patients are suffering needlessly because companies pick and choose where it is more profitable to launch their drugs.

“We have a first, second and third class of European citizen when it comes to access — that’s a scandal,” says Clemens Auer, who was director general of Austria’s health ministry until 2018.

Drugmakers demand higher prices each year, often with discounts already priced in, says Joerg Indermitte from Switzerland's Federal Office of Public Health “The last example I have is 50,000 francs [€51,800] per month for a new oncology drug. We never had such a high price. Although only 10-20 patients are treated with this new drug, it is extremely expensive.”

Investigative Europe reporters spoke to dozens of officials involved with confidential pricing who described an “absurd” system that forces them to negotiate medicine prices blindfolded.

“Price secrecy is considered a core value of the industry,” says Wim van Harten, a Dutch oncologist who has spent years looking for the true costs of cancer therapies in Europe.

Rich nations generally pay less than those in central and eastern Europe for certain drugs, the investigation finds. It reveals an alarming gulf in access across the bloc to many innovative medicines, while drug firms rack up vast profits from healthcare systems.

The official price of a drug — its ‘list’ price — can easily be found online or on the back of medicine packs. But these prices are often artificial, and it is in the industry’s interests for them to be high.

The reason is simple: dozens of countries set their prices by looking at what other states publicly say they pay – be it cancer treatments with list prices in six figures or rare single-dose drugs marketed in their millions. High list prices are the industry’s gateway to bumper profits.

In reality, a parallel system exists.

The parallel system

The European Medicines Agency approves certain categories of drugs for use across Europe. Companies then choose whether they want to market a drug in a country or not.

The official price is set by each country separately and then individual negotiations begin to agree on any secret discounts. Pharmaceutical firms effectively get billions in what experts call ‘interest-free loans’ as most states at first pay them the higher official drug price.

Then, over time, companies discretely return the difference between the official price and the real, negotiated price. In Belgium alone, these returns amounted to €1.5bn in 2023. In bigger markets, the rebates are larger, and the amounts of public money temporarily loaned to industry are even higher.

Industry is “adamant on keeping the results of these negotiations secret,” says lawyer and public health advocate Ellen ‘t Hoen. “Having all couched in secrecy gives them an enormous power to play a divide-and-rule game.”

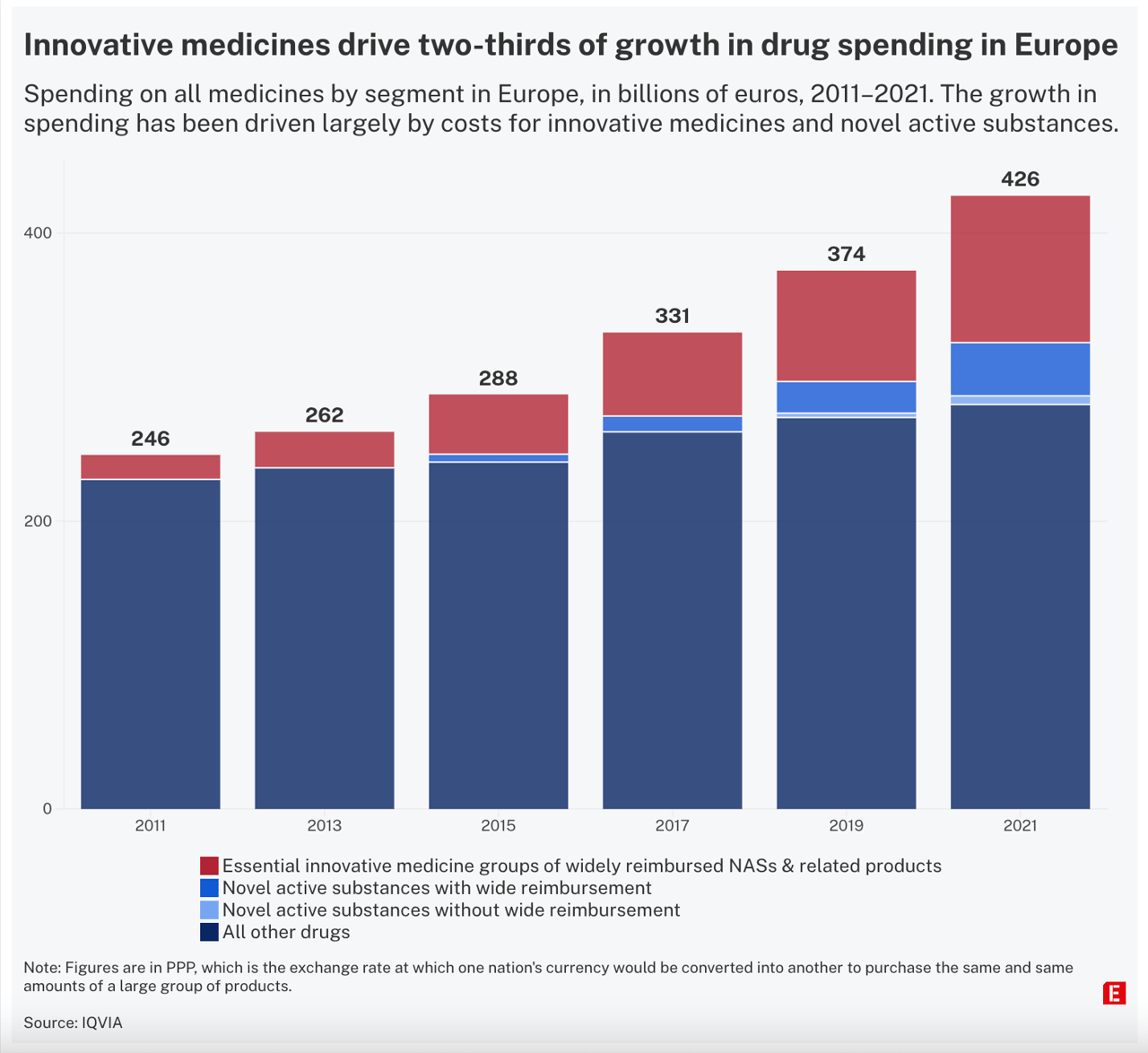

Countries strike secret deals hoping to contain the rising costs of new drugs – but innovative drug prices are rising everywhere.

In the Netherlands, the part of the national hospital budget spent on these drugs has risen from 0.6 percent to 10 percent in the past 15 years, Dutch oncologist van Harten says.

Norwegian authorities say they had to rebuild their database to give room for more zeroes in million-figure prices. The company Novartis broke the record with Zolgensma, a treatment for spinal muscular atrophy, which they set at 27m NOK [€2.3m] — an "absolutely unethical” price, says Anja Schiel from Norway’s Medical Products Agency. Ultimately, a confidential rebate was agreed upon in 2021.

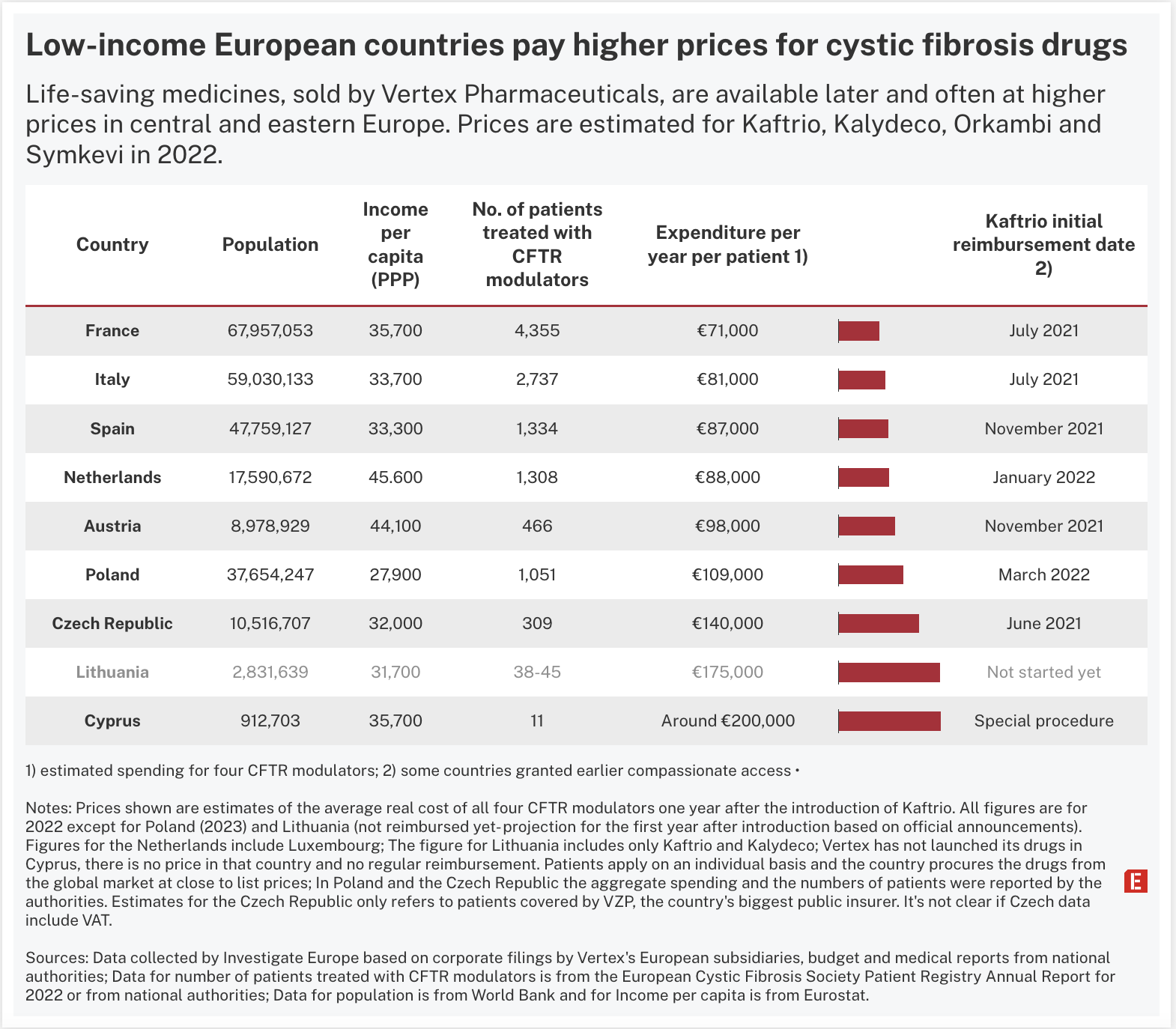

Investigate Europe analysis indicates that countries across Europe are paying wildly different prices for 'miracle’ cystic fibrosis drugs.

Vertex Pharmaceuticals, the US biotech firm with a monopoly on the treatments, can ask for more than €200,000 per patient per year for its breakthrough Kaftrio/Kalydeco treatment – more than 40 times the estimated production cost, according to UK researchers. The firm disputes this, saying that prices are not determined by production costs, but by the investment made in their development, the risk undertaken, and their value to the community.

The medicines have been lauded for helping patients with the rare disease that progressively clogs the lungs and can lead to early death. Yet Vertex, which had sales of almost $10bn in 2023, appears to be charging poorer nations higher prices than some of their richer neighbours.

Analysis of corporate records and budget and health data from national authorities provides for the first time a glimpse into the disparity in what countries pay for these life-saving medicines.

Patchy prices across Europe

In western Europe, Investigate Europe compared Vertex's local revenues to the official number of patients taking the company's drugs in 2022. The average, excluding VAT, was estimated to be around €71,000 in France, €81,000 in Italy, €87,000 in Spain and €88,000 in the Netherlands.

In comparison, the average expenditure per patient in some central and eastern European countries appears higher. In the Czech Republic, the estimated yearly cost in 2022 was €140,000, according to data from VZP, the country's largest public insurer. "This is the real cost paid for this kind of treatment," VZP said, though it is not clear if any tax is factored in.

Lithuanian authorities have spent years trying to negotiate with Vertex amid mounting pressure from the media and patient groups. The government said in April that it was ready to pay as much as €8.4m to provide Kaftrio and Kalydeco for up to 48 patients. This could equate to €175,000 per person.

“The inverse correlation between numbers of patients and prices likely reflects differences in negotiation powers,” says Valérie Paris, economist at the OECD who has worked extensively on pharmaceutical pricing. "It seems to me that you have made all possible efforts to get net prices but only the company selling the product or national authorities could really confirm these data.”

Monika Luty, 27, was forced to leave Poland in 2020 because the drug was not reimbursed there. She posted a video online, begging Vertex to give her Kaftrio. "I felt a huge disappointment," she says. "Living in the EU, being Polish, I was discriminated against because I was not German or of another nationality where treatment was available. There should be no discrimination in the EU."

Her friends helped her crowdfund over €200,000 and her dad sold his car so she could buy the drugs from Germany. Seeing how effective they were, she crossed the border for good. "I paid zero, so I was crying because it was so easy," she remembers. "To get the drugs in Germany, all I needed was insurance, a job and to live there."

Poland later struck a reimbursement deal with Vertex and Investigate Europe estimates that the price per patient in 2023 was €109,000 before VAT. Far cheaper than the Vertex list price, but still more expensive than elsewhere in Europe.

“The price of our medicines is based on their innovation and the value they bring to the CF community, caregivers and healthcare systems," a Vertex spokesperson said. "The reimbursed prices quoted in your inquiry are inaccurate." The company declined to comment on individual countries or to specify the inaccuracies. It added that over the past decade more than 70 per cent of its operating budget was spent on research and development.

Despite its huge revenues, Vertex is not part of Europe’s main industry body. When asked about confidential pricing, the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations did not directly answer whether richer countries are paying more than poorer ones.

“There is a broad consensus that prices need to reflect the ability of a country to pay for medicines. Efpia and its members propose a system for Europe where countries who can afford to pay less for medicines, pay less,” says Nathalie Moll, its director general.

Strategic threats

A typical strategy to maintain the secrecy status quo is the threat to boycott markets.

“I have done hundreds of these negotiations,” says Francis Arickx, head of pharmaceutical policy at the Belgian National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance. “The threat that the company is not going to sit at the negotiating table, we hear it all the time and we hear it everywhere.”

KCE, a state-funded institute in Belgium, tried in 2016 to examine the secret discount deals signed by national authorities. They wanted to present results without divulging any protected data about specific deals. Yet after pressure from the Belgian Pharmaceutical Association, a watered-down study was released, excluding any analysis of those deals. The study did however reveal that the association had threatened to sue prior to publication.

When a big Swiss drugmaker pushed for a higher price in Austria, Clemens Auer alleges that a representative reminded him of the investments they had made there, implying that those were at risk if a favourable deal was not agreed. “It's always the same stupid, very primitive game,” he says.

Denmark and Germany, two countries that allow companies to initially set official prices freely, are usually the first entry points in Europe.

In practice, Denmark places some ‘voluntary’ price limits, while Germany reviews each medicine one year after introduction and can then ask for price changes. Meanwhile, the initial high prices are used as a reference by others, while setting their own official prices. What happens next in the two countries is shrouded in secrecy. Danish hospitals procure the most expensive medicines with confidential discounts, but these deals do not appear on Euripid, the European pricing database, Danish officials say.

Germany is even more opaque. It vetoed a World Health Organisation resolution on price transparency and it is not even part of Euripid.

“We always ask the companies ‘tell us, please, the real price in Germany’. They say they don’t know,” says one European negotiator, who requested anonymity. “I just can’t believe [there are no confidential discounts] because they have a really powerful market, they could get the best prices in Europe. Maybe it’s possible but I really can’t believe it.”

The rest of Europe is starting from a step behind. A pharmacist working for a Hungarian subsidiary of a multinational drugmaker puts it bluntly: "For a company like Novartis or Pfizer, the Hungarian market is a rounding error.”

Worst situation in Hungary, Malta and Cyprus

Investigate Europe found that Hungary is among several states locked out of access to critical medicines.

German research institute IQWiG compiled a list of 32 medicines for Investigate Europe and its German partners NDR, WDR and Süddeutsche Zeitung. These drugs, according to the scientists, have a "significant" or "considerable" additional benefit to existing therapies. They included treatments for conditions including breast cancer, leukaemia and cystic fibrosis.

Data collected from across Europe reveals that in six EU countries one-in-four of these important medicines is missing. Without purchasing agreements between countries and companies, which are the basis for reimbursement, health authorities have to resort to other costly methods to obtain a drug, or miss out on access altogether.

The situation is particularly dramatic in Hungary, where 25 out of 32 medicines are not available, and in Malta and Cyprus, where 19 and 15 medicines respectively are not generally reimbursed. Patients in Cyprus and Hungary can get some drugs by applying for individual access – but often at extortionate costs to the state. In the Baltic states and Romania, a high number of important medicines are also unavailable.

Even when medicines are made available to smaller states, prices can be excessive.

Giorgos Pamboridis, Cyprus’s former health minister, occasionally discovered that their prices were “double, triple or even five times those paid by other countries”. He is appalled that the EU allows industry to treat its members so differently. “NDAs [non-disclosure agreements] are tools for the abuse of dominant position that industry has vis-a-vis its clients, the states. Without the slightest consideration, the EU is giving up on its sole advantage, its size.”

Siloed negotiations amplify inequality, says a former Irish health official: "The 27 member states negotiating for themselves is astonishingly inefficient and leads to inequality for European citizens.”

When 10 countries including Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal and Spain joined forces and signed the Valletta Declaration to cooperate on medicines procurement in 2017, industry showed zero interest, several participants told Investigate Europe.

Further north, the Beneluxa collaboration – Austria, Belgium, Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands – has negotiated prices for a few high-cost drugs, mostly with small firms. Two negotiators involved said bigger companies are reluctant to join.

“The small companies say, ‘yes, with one negotiation I can access more markets, so I agree’, while the big companies seem to be boycotting this kind of initiative,” says Paolo Pertile, an economics professor at the University of Verona.

Covid-19 case

The one-time major companies negotiated EU-wide was for Covid vaccines. It showed that if pressured, industry can conceivably agree to not play one country against the other. But prices again were secret. “If the EU had used its joined forces to not agree to confidentiality clauses, this could have been a game changer,” says Sabine Vogler, head of pharmacoeconomics at Austria’s national public health institute.

Pharmaceutical companies are able to “blackmail governments”, says Luca Li Bassi, former head of the Italian Medicines Agency, who has campaigned for greater price disclosures. “If transparency is demanded, the pharmaceutical companies threaten not to give the drug.”

Meanwhile, the suspicion that every time there is a confidentiality agreement, someone else is being ripped off, was proven right when the price of the AstraZeneca Covid vaccine was leaked. In South Africa it was double that of the EU.

“Any member states’ collaboration... should guarantee the confidentiality of pricing and reimbursement agreements,” Efpia’s Moll says. “Industry participation in any member states’ collaboration on pricing, reimbursement and access-related issues should be voluntary.”

The idea that industry is the only real winner of this secrecy is widespread among negotiators like Francis Arickx, who says Belgium tried and failed to limit confidential clauses. “The opposite actually is happening; we see a very clear industry push to maintain contracts until generics or biosimilars arrive.”

EU health commissioner Stella Kyriakides is aware of the myriad issues. "Where you live shouldn't determine whether you live or die," she said when presenting a new set of laws last year. But the EU’s planned ‘pharma package’ legislation has been met with resistance. It includes no measures to tackle secrecy or confidential prices. Even an attempt to reduce market exclusivity of pharmaceutical firms was clipped by industry and member-state lobbying.

“Medicine prices are an area of national competence and linked to national health budgets,” a European Commission spokesperson told Investigate Europe. “However, as acknowledged in the Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe, greater transparency around price information could help member states take better pricing and reimbursement decisions.”

The spokesperson said that the commission supports the work of Euripid, the European pricing database. Yet when contacted, Euripid refused to provide any data on the rising number of confidential agreements between states and pharmaceutical companies.

Now the veil of secrecy could become even thicker. A new law for “Medical Research” is under discussion in the German Parliament. If it passes, every time authorities order a price cut because a drug does not perform as promised, the rest of the world will not know. The artificially high ‘official’ prices are all they will see. Industry will be thrilled if it happens, says Josef Hecken, head of the national committee for approving new drugs. “Medicines that get steep discounts here will be sold elsewhere as gold,” he says. “Champagnes will pop in many corporate offices.”

This article is a co-publication with Investigate Europe.

Author Bio

Eurydice Bersi, Lorenzo Buzzoni, and Maxence Peigné are investigative journalists for Investigative Europe. Ingeborg Eliassen, Harald Schumann, Nico Schmidt, Attila Kalman also contributed to this piece.

Tags

Author Bio

Eurydice Bersi, Lorenzo Buzzoni, and Maxence Peigné are investigative journalists for Investigative Europe. Ingeborg Eliassen, Harald Schumann, Nico Schmidt, Attila Kalman also contributed to this piece.