Interview

The Renaissance Italian villa where the EU archives its history

Villa Salviati is a beautiful renaissance residence rising on the green hills above Florence in Italy. From this place powerful aristocratic families have pulled important strings for almost 500 years.

“It’s geographical location meets all the requirements regarding the perfect setting of suburban residence,” according to the official brochure about the villa.

“Hilly, rich with water, sunny, suitable for agricultural activities, near the city centre and with a panoramic view”.

But despite the heavenly surroundings, the owners could not find a private investor when they wanted to sell the estate back in 2000.

And so “the Italian state bought Villa Salviati with the view of giving it to the European University Institute as the seat to the Historical Archives of the European Union (HAEU)," says Dieter Schlenker, holding the keys to Villa Salviati today, as director of the archives.

After years of renovation, the archives moved into the premises in 2012.

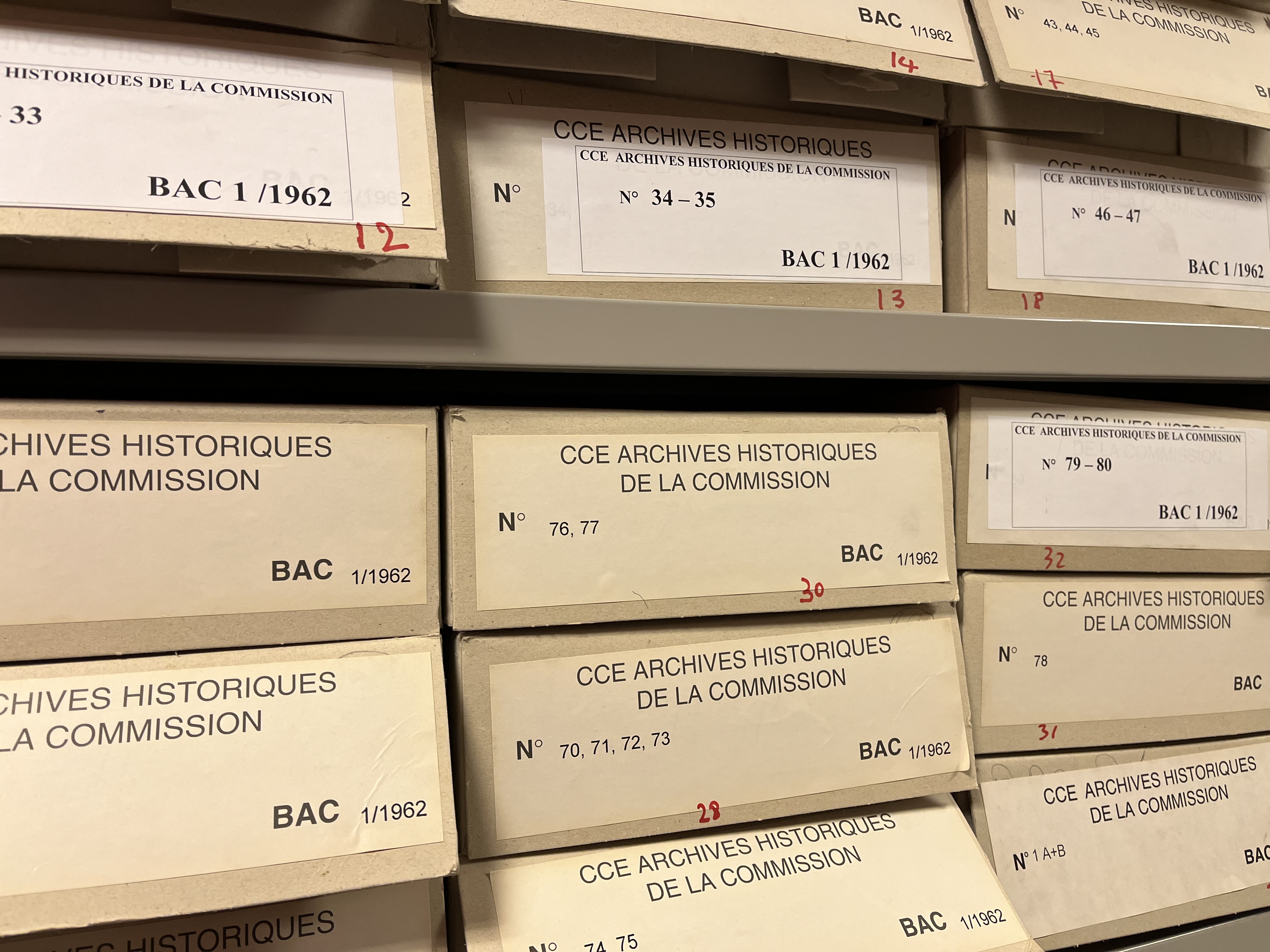

EU documents are shipped to Villa Salviati and made public 30 years after they were produced in the EU institutions (Photo: EUobserver)

Thanks to the British

When the EU started in the 1950s, there were no rules about storing documents or giving people access to them. This practice started only in the 1970s after the UK joined and Roy Jenkins became president of the European Commission (1977-81).

“The British came with a certain reform spirit. They introduced new administrative processes in the commission, changing slightly the French culture. Creating historical archives was part of the new culture,” says Schlenker.

Born in Freiburg, Germany, Schlenker began his own career as an archivist in Italy working for Catholic charity Caritas and the Vatican archives. He also worked at UNESCO’s headquarters in Paris.

EUobserver asked him why the EU needs historical archives.

“Every organisation needs to protect its legal rights. If the original treaties, international agreements, acts, correspondence and decisions are gone, the Union is gone,” he says.

Another major reason to archive is knowledge and understanding of history, he continues.

Interest in European integration is growing with time. The more time that has passed and the more the European Union project has become a reality, the more people want to look into the history of it.

"The European Union is today integral to all the policies shaping the member states. Particularly since the time of Jacques Delors (commission president 1985-95), it is so much integrated with national policies that all the studies, historical studies, in whatever field ... the researchers always need to combine the two. We have on one side studies on European integration itself — but we also have a lot of history written about European policies in connection with national policies, external relations, enlargement and so forth. This is the second reason.”

A third reason for running the historical archives is the citizens themselves, Schlenker says.

“There is a clear right in the European Union and its member states called the freedom of information, which means that every European citizen has the right to access the decisions of the institutions. This has been a regulation since 2001, so basically every citizen can go and consult it. It’s a right and in the interest of the citizens.”

The 30-year rule

The EU documents are shipped to Florence, and then made public 30 years after they were produced by the EU institutions. But only 20-30 percent of the total amount of documents make it into the historical archives, according to Schlenker.

“The weeding is done within the institutions themselves. It is a tradition in Europe that the owner, the producer of the archives, will be responsible until the material can go public — whether it goes to the national archives, or, in our case, to the EU historical archives.

“A lot of documents are [actually] destroyed much earlier. For example, financial papers, such as bills, commitments, procurements and alike that have no historical value. After 10 years, when all the audit controls and checks are through, this is all destroyed. It is a big chunk of documentation".

“Personal files stay within the institutions for up to 100 years. Staff matters, they are confidential and have to stay in the institution for the time that the person is employed but then also a long timespan afterwards — for any claims on pension, medical questions, heirs and so forth. They only reach us after 100 years. It won’t happen during my period to see these files”, Schlenker smiles.

Commission backlog

The sheer volume of papers in Florence demonstrates how EU powers have grown over the years.

Some 10km of documents have been shelved in Villa Salviati to date, which is less than, for example, Luxembourg would have in their national archives, according to the EU’s chief archivist.

But soon — by the end of the next decade — the European Union’s historical archives will have doubled to more than 20km, he estimates.

The commission produces more files than any other EU institution, with more than 100km of documents piling up in a warehouse close to Brussels.

Only 5-10 percent of these files will eventually become part of the historic archives in Florence, according to a promotion video from the Commission.

Most of the institutions are able to keep their own materials in-house until they decant them to Florence.

“The only one that really has a considerable backlog is the Commission due to the sheer quantity of files it produces compared to the small archives unit that deals with the materials”, Schlenker says.

“In the case of the commission, it’s usually one or two trucks [coming to Florence] per year with each time around 20-30 pallets, so that’s big – some 300 metres each year. And then another 100 metres from the other institutions, so we get on average 400-500 meters per year”.

The commission produces more files than any other EU institution, with more than 100km of documents piling up in a warehouse close to Brussels (Photo: EUobserver)

No EU acquis for archives

Not all EU-related documents of historic interest end up in Florence after 30 years, however.

“The European People’s Party Group in the European Parliament would have been created in the early 1950s and they would deposit with the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung [Institute]. Similar with the Greens. They went to deposit at the German Green Foundation before our archive came into place”, Schlenker explains.

Archiving also follows different national traditions.

“The British officials often deposit their archives in the university where they have been educated. German politicians sign a deposit agreement with their party foundation. If they later become chancellor or member of the German parliament or member of the European Parliament or the Commission or whatever, their personal archives go systematically to the German foundation”.

“The French don’t have a strict system, which is why various French EU officials would deposit their archives in Florence. And the same for the Italians”, Schlenker says, adding: “I obviously regret it, but there is no EU acquis communautaire for archives”.

Even with 20km of archives at the end of the 2020s, the EU will still be dwarfed by the Vatican archives’ 85km of shelving.

“The Vatican is famous for its registry books. They invented a system of abbreviations, and acronyms, so basically, they shrink the text to something like 10 percent through formulas, which you have to dissolve, otherwise, you can not read it. Like coding. Very fascinating. They basically document all in and out correspondence of the Holy See. It started in the 11th century, then there are gaps here and there, but from the 13th century onwards it is complete until today. This is enormous”, recalls Schlenker, who studied and worked in the archives in his youth.

“The Vatican would have dedicated staff that would go into the deposits, while we as researchers would just be delivered. You need to understand the system and the coding and the system they use, which is quite complicated. Still, you can find the information.”

Von der Leyen emails

With files moving online, there will be less need for trucks in the future to transport documents from Brussels to Florence. But then other problems lurk.

“The first challenge will be the transition period because now we have hybrid archives. We are entering times where archives are partly electronic and partly paper. Sometimes it overlaps. Sometimes there are gaps”.

“The challenge is to find a new balance between quality and quantity. People write through tweets, through WhatsApp, through letters and emails. This is more tricky. The unstructured documentation makes archiving more difficult in the digital world”, says Schlenker.

“When the digital world came … one new concept was that we do not need to do the selection any more. We can just keep it all. But, in fact, nobody can do that, because even with AI and search engines, it is not possible to manage all the information created. Digital long-term storage takes so much energy and space, this is just not manageable,” Schlenker says.

All archivists work to preserve their archives and to keep them safe and organise the information so it can be retrieved.

In Florence, the EU files are kept underground in fire-protected compacts shelves with only dedicated staff given access, just like in the Vatican.

But this is not the only security measure.

“All international organisations - including us and obviously the Vatican – have privileges and immunities. We have protection levels beyond the Italian legal framework”, Schlenker explains.

“And we keep all the documents on-site. We have our own shelves and our own servers, the archives are not in the cloud".

There has been much discussion about EU commission president Ursula von der Leyen's emails. Do you think personally her emails should be stored? EUobserver finally wanted to know.

“In principle, email is similar to a letter, and official email should be kept”, Schlenker says, adding:

“Archiving rules in organisations should say that whatever official document you create as an officer of our organisation will go into the archives and historically relevant email should be open to the public after 30 years.

"Much email is still considered as peripheral to support official documentation — but not as a record per se”.

By the end of the next decade the European Union’s historical archives will be doubled to more than 20km, estimates director Dieter Schlenker (Photo: EUobserver)

Author Bio

Lisbeth founded EUobserver in 2000 and is responsible to the Board for effective strategic leadership, planning and performance. After graduating from the Danish School of Media and Journalism, she worked as a journalist, analyst, and editor for Danish media.

Tags

Author Bio

Lisbeth founded EUobserver in 2000 and is responsible to the Board for effective strategic leadership, planning and performance. After graduating from the Danish School of Media and Journalism, she worked as a journalist, analyst, and editor for Danish media.