Analysis

Georgia and Moldova vote — but to go East or West?

In the coming week, a crucial decision beckons for two European countries that were once part of the Soviet Union. What is their vocation on the geopolitical chessboard? Should they continue on their chosen path of rapprochement with the West and the European Union, or is it time to return to the fold of Moscow?

It may seem like an extreme simplification, but this is the binary choice faced by Georgia and Moldova. Along with the outcome of the Ukraine war, the decisions of these two countries will determine the contours of tomorrow's Europe.

On 20 October, Moldovans will vote in the first round of a presidential election and choose by referendum whether they wish to amend the constitution to allow their country to join the EU.

Six days later, Georgians will elect their parliament and so decide whether to put an end to 12 years of government by the populist pro-Russian Georgian Dream party and return the country to the hands of the pro-European opposition.

The polls give a clear lead to the incumbent Moldovan president, the pro-European liberal Maia Sandu, over rival candidates.

Her strongest opponent is the former prosecutor-general Alexandru Stoianoglo, who is the candidate of the Socialist Party of the pro-Russian former president Igor Dodon.

As for the referendum, the same poll gives a two-thirds preference to the 'Yes' side, in line with a similar figure in favour of Moldova joining the EU (63 percent). But in the event that the pro-European side does not win, the pro-Russian or "sovereigntist" parties will promote a rapprochement with Moscow. In its wake would likely come repressive legislation inspired by the Russian law on foreign agents, as has happened in Hungary, Bulgaria and Georgia.

In Georgia, the situation is more complex. In recent months, the positions of the government and the opposition parties have hardened. The ruling party, Georgian Dream (KO), is being manipulated in an increasingly secretive manner by the party’s founder and the country's richest man (his fortune is estimated to represent almost 30 percent of the national GDP), Bidzina Ivanishvili.

While continuing to advocate closer ties with Europe, the government is adopting measures that have seemingly been lifted straight from the Kremlin's handbook for authoritarian regimes.

Georgia's recent law on "foreign agents" and the law adopted in September 2024 to ban "LGBT propaganda" are so incompatible with EU membership that Brussels has suspended the accession procedure launched in December 2023.

The aim of the laws, like their originals in Vladimir Putin's Russia, is to crush civil society and thus root out dissent. The de-facto side effect: Georgia's distancing from the West and its rapprochement with Moscow.

Most of Georgians want to join the EU

Such an outcome is clearly not desired by most Georgians. Almost 90 percent of them want to join the EU.

And yet the less attentive among them are vulnerable to the rhetorical gymnastics of the ruling KO. The party claims to be pursuing EU membership (its ubiquitous campaign logo even features the European flag), all while it makes repeated gestures of goodwill — and even submission — towards the Kremlin. To the point that several KO members have been targeted for sanctions by the United States.

KO is credited with around 33 percent of the vote by the most recent polls. To oppose it, civil society and the opposition have come together in a united front. More than 99 percent of the organisations (small associations, NGOs and independent media outlets) targeted by the so-called Russian Law have refused to register as "foreign agents".

This puts them at risk of heavy fines, but they are betting on an end to the reign of Ivanishvili's party. Once split between various movements with diverging leanings, the political opposition has regrouped into a handful of informal coalitions. The sum of their votes is likely to approach 50 percent, according to the aforementioned polls.

Georgia's president, Salome Zourabichvili (an independent), has used all the levers at her disposal to secure the country's European foothold.

Her "Georgian Charter" aims to provide a roadmap for the pro-Western opposition to the Georgian Dream. The document proposes that, following the elections, a technical government should ensure the democratic transition and implement the reforms necessary for EU membership. 19 parties have signed up.

KO is playing the card of division, posing as the guarantor of traditional values (it enjoys the support of the Orthodox Church) against pro-Western liberals. Firstly, prime minister Irakli Kobakhidze announced the banning of the opposition coalition after the elections, then Ivanishvili accused it of wanting to "open in Georgia a second front" of the war in Ukraine.

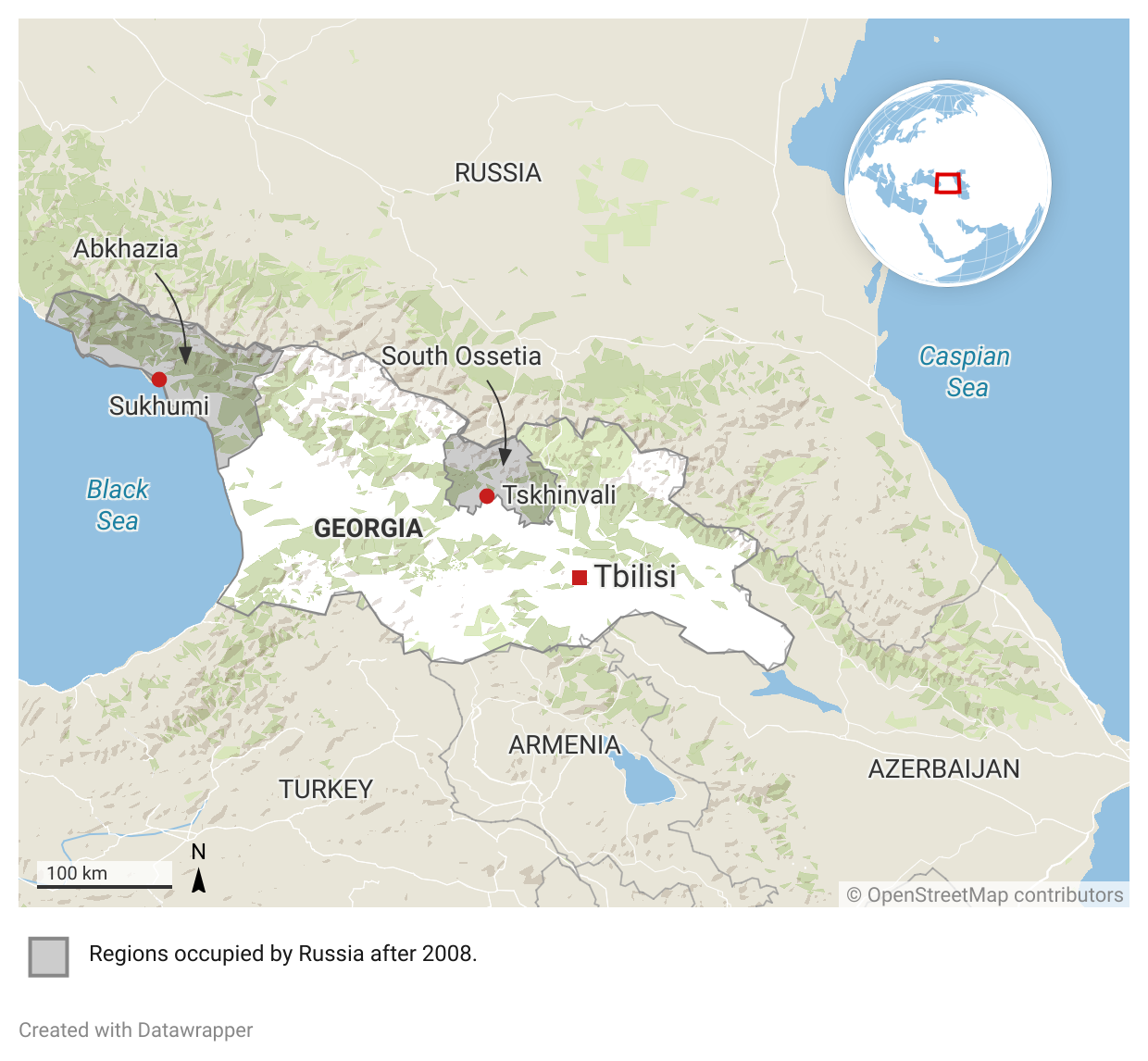

Georgia has things in common with Ukraine: both countries were once unwilling republics of the USSR, and both are now occupied by Russian or pro-Russian troops (in 2008, Moscow invaded the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia: Tskhinvali for the Georgians).

KO thus leverages Georgians' fear of being dragged into the conflict across the Black Sea by what it calls the "World War Party" – the Western coalition that is backing Ukraine against Russia. And yet, to judge by the plethora of Ukrainian flags and anti-Russian graffiti on the streets of Tbilisi, the Westerners' solidarity with Ukraine is shared by a large number of Georgians.

With the ostensible purpose of sparing Georgia the fate of Ukraine, the Georgian Dream seems to have made a pact with the Russian devil. The party's mafia-like methods of intimidation appear inspired by the FSB, the Russian security agency, observes Marika Mikiashvili, a researcher and member of the liberal Droa party. For months now, opposition figures and their families have been receiving anonymous phone calls of varying degrees of menace.

They have been followed in the street, beaten up by groups of masked thugs, and subjected to defamation campaigns. The latter has taken the form of posters with their picture and the word "traitor", plastered onto their homes or workplaces. Such methods “are very different from what Georgians are used to, with a level of physical and verbal violence that has never been seen before", notes Mikiashvili.

Georgia's civil society has responded in kind. The largest protests in Tbilisi since independence in 1991 saw hundreds of thousands of people take to the streets to demand the withdrawal of the draft "Russian law". The movement’s leaders were of the Gen-Z age. Their spirit of independence, creativity and solidarity made an impression both in Georgia and abroad.

The Venezuela scenario

For its part, the Georgian Dream naturally denies any form of coercion. It claims to be confident of victory, despite the evidence.

PM Irakli Kobakhidze and media outlets close to the government repeat that KO is polling at 60 percent. That figure is “beyond ridiculous", according to historian Beka Kobakhidze (no relation to the prime minister). "They have never received 59 percent of the vote and certainly not now, after so many months of protests and anti-Western and pro-Russian policies from their side."

However, Beka Kobakhidze emphasises the risk that KO will rig the elections and declare itself the winner regardless of the result. He points to the Venezuelan scenario (in which president Nicolás Maduro has repeatedly validated unfair elections on his path to dictatorial rule). "Worrying signs point in that direction", remarks Kobakhidze.

“[KO] has changed the electoral law such that the government can now certify the results without involving the opposition. They have put up a three-metre-high wall around the headquarters of the electoral commission and removed the paving stones in the streets adjacent to the parliament for fear that any demonstrators might make use of them, as happened in Kyiv during the Maïdan uprising in late 2013. They have the police, the judiciary and the electoral commission under their thumb. So the Maduro scenario is plausible."

Yet, if such protests do erupt,"it is likely that the government will be reluctant to use violence along the lines of the Russian model", believes Marika Mikiashvili.

"Georgia is a small country; everyone knows everyone else and what is considered violence in Georgia might not even be considered violence elsewhere. We are not habituated to violence. Here, burning a car during a demonstration is quite exceptional. Last year, we saw the first Molotov cocktail since the clashes that preceded independence [in 1991]. If by some chance the government were to start firing on crowds, most of the police officers would come under irresistible pressure from society, from their own relatives and families, " Mikiashvili says.

The stakes in the elections go beyond Georgia, she says.

"Experts agree that Georgia now is on the frontline of civil liberties in the wider region, starting from, well, maybe even some EU members" — an implicit reference to Hungary and Slovakia. "If Georgian Dream stays in power this year and beyond, it will be a huge confidence boost for other illiberals in Europe and especially in the enlargement area to [encourage them to] proceed with whatever laws and actions they want."

Particularly vulnerable is neighbouring Armenia, another former Soviet republic with a complicated relationship with Russia. In the recent regional conflict, Armenia lost the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh after Moscow withheld its military and diplomatic support.

"The victory of Georgian Dream would [thus] endanger the physical integrity and democracy of Armenia, which would find itself encircled by pro-Russian autocratic regimes", observes Marika Mikiashvili.

The Ukrainian scenario

And in the event of an opposition victory, should we fear a scenario similar to that of Ukraine in 2014, when Russia invaded? Beka Kobakhidze cautions against the comparison:

"Some representatives in the Russian Duma [parliament] have said that Russia is ready to intervene militarily if KO were to ask for its help. But I don't see how that could happen, because Georgia is not Crimea. Georgians generally dislike Russia, to put it mildly. Russia has lots of hybrid mechanisms available and I believe they'll go for that option."

"I don't know what the outcome of this election will be", says the writer and opposition figure Lasha Bakradze.

"What I know is that it will be neither fair nor free. But we must fight because this is not a normal election. It is a referendum on the future of Georgia. Do we want to live in a country like Russia, with no freedom of expression? Or do we want to be part of the Western community and, in the future, the EU?"

This article was originally published on Voxeurop. It was produced as part of the PULSE project, a European initiative supporting cross-border journalistic cooperation. Contributions by Mila Corlateanu of n-ost (Germany).

Author Bio

Gian-Paolo Accardo is the editor-in-chief of Voxeurop, the co-founder and CEO of Voxeurop European Cooperative Society and the editorial coordinator of the European Data Journalism Network.

Tags

Author Bio

Gian-Paolo Accardo is the editor-in-chief of Voxeurop, the co-founder and CEO of Voxeurop European Cooperative Society and the editorial coordinator of the European Data Journalism Network.