Explainer

The turbo-charging of EU defence — explained

Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 shook the EU's approach to defence, prompting a swift reevaluation of the EU’s military landscape.

As the European Commission sets out its vision for a single market for defence in its white paper due on Wednesday (19 March), we take a close look at global and European trends — and the industry’s readiness to meet new challenges.

Which are the countries spending most on defence in the world?

The countries with the highest defence spending in recent years are the United States, China, Russia, India, and Saudi Arabia. European growth is outpaced by Russia's rising military spending, which has more than doubled the levels before its 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

How much do Nato members spend on defence?

US president Donald Trump has repeatedly criticised allies for not meeting the alliance’s defence spending target of two percent of GDP (agreed upon back in 2014). Even now, Croatia, Portugal, Italy, Canada, Belgium, Luxembourg, Slovenia, and Spain have not hit the target.

The defence spending of the 23 EU countries that are Nato members amounted to 1.99 percent of their combined GDP in 2024 and is projected to reach 2.04 percent in 2025.

But Trump suggested that Nato members should increase their minimum defence spending to five percent of GDP — an idea backed by EU foreign affairs chief Kaja Kallas in January. Macron has proposed raising the EU's defence spending by three to 3.5 percent of GDP. Yet, this would take years to materialise based on current rates.

Defence is a tech-driven industry that calls for massive investment in research and innovation. Defence R&D funding in the EU reached €3.9bn in 2022, according to Eurostat. However, according to the Dragi report, next-generation defence systems will require massive R&D investment. Since 2014, the US has prioritised R&D spending above all other military expenditure categories. France, Germany and Sweden are at the top of EU countries investing in R&D for defence.

Which European countries are increasing defence budgets the most?

Since 2014, countries such as Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland, Denmark, North Macedonia, Slovakia, and Sweden have doubled their defence expenditures, while Luxembourg, Latvia, and Lithuania have tripled their spending. Germany, the Netherlands, Estonia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Finland have also nearly doubled their defence budgets.

How many soldiers do European countries have?

The total number of active military personnel in Europe, including the UK, is estimated to be around 1.5 million. However, its efficiency is undermined by the lack of a common command structure and military systems.

By the end of 2024, the number of Russian troops in Ukraine was approximately 700,000. However, it is estimated that Russia has about 1.3 million active military personnel and two million reservists.

According to official figures, around 80,000 American military forces are active in Europe. However, the total number fluctuates due to exercises and routine troop rotations, as noted by the Council on Foreign Relations. Meanwhile, experts estimate Europe would need an additional 300,000 servicemen or around 50 brigades to defend itself, without US troops.

Is compulsory military service back in Europe?

With the Cold War over, many EU countries significantly reduced their military personnel, since conscription was abolished in many countries. For example, France ended it in 1997 and Germany in 2011.

However, in response to the growing Russian threat, countries like Latvia and Lithuania have reinstated conscription in recent years. To strengthen European armies, Latvia's president Edgars Rinkēvičs recently said Europe should “absolutely” introduce conscription, an idea backed by Estonia.

Several European countries do still have compulsory conscription, ranging from four months in Denmark to 19 months in Norway. Austria, Finland, and Sweden require six to 12 months, while Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania mandate around nine to 11 months. Greece and Cyprus have longer terms of 12–15 and 15 months, respectively.

Is Europe moving towards a joint army?

No. Some countries, like France, have traditionally supported stronger EU military autonomy, while others, such as Poland and the Baltics, prioritise Nato. But rather than moving toward a single European army, the EU is focusing efforts on closer military cooperation, joint procurement, and faster response forces, as seen in the 2022 Strategic Compass, whose goal was to have a 5,000-strong rapid deployment force by 2025. Military mobility is still today one of the priorities of the EU’s defence strategy since no harmonised rules to move troops or equipment between countries in a situation of emergency.

Why and how does the EU plan to boost its arms production?

The invasion of Crimea in 2014, followed by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, has reshaped EU security policy, forcing the EU and Nato to rethink defence strategies and increase military spending to boost capabilities. The war in Ukraine and the Trump administration's apparent pivot towards Moscow has also revived discussions on EU strategic autonomy, with France (and now even Germany) pushing for more independence from US-led security structures.

Over the past two decades, the EU has come up with different defence initiatives.

Key steps to enhance military collaboration include the set up of the European Defence Agency (2004), its annual Capability Development Plan (2008), and PESCO (2017). Regulations for defence transfers and dual-use exports have also strengthened arms control, while Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine accelerated EU defence efforts, leading to the creation of the European Peace Facility (2021), EDIRPA, ASAP (2023), and EDIS (2024).

With its ReArm Europe plan, the European Commission aims to mobilise €800bn to boost EU defence spending, support Ukraine, and expand Europe’s industrial base.

The plan includes a new instrument of €150bn in new joint EU borrowing, loosening the bloc’s fiscal rules for defence (which could be freed up €650bn over the next four years), using cohesion funds (voluntarily), changing investment rules for EIB and “unlocking private” investment throughout the long-stalled Capital Market Union (CMU).

How big is the EU’s defence industry?

The EU defence sector has an estimated annual turnover of nearly €84bn, directly supporting over 196,000 high-skilled jobs and indirectly creating more than 315,000 additional jobs, according to the European Commission. But the European defence industry needs more skilled workers as it boosts production and innovation to tackle growing security challenges.

European defence companies' market values have soared, with most doubling their share prices since Russia invaded Ukraine. But revenues are still pretty small, showing that their capacity to scale up is held back by the size of national markets and export restrictions. This has prompted a debate about whether there should be a European preference for common EU defence spending. “Such ‘European preference’ is a necessary contribution to reverse the current predominance of non-European suppliers on European defence markets,” argues the industry. But EU countries remain divided.

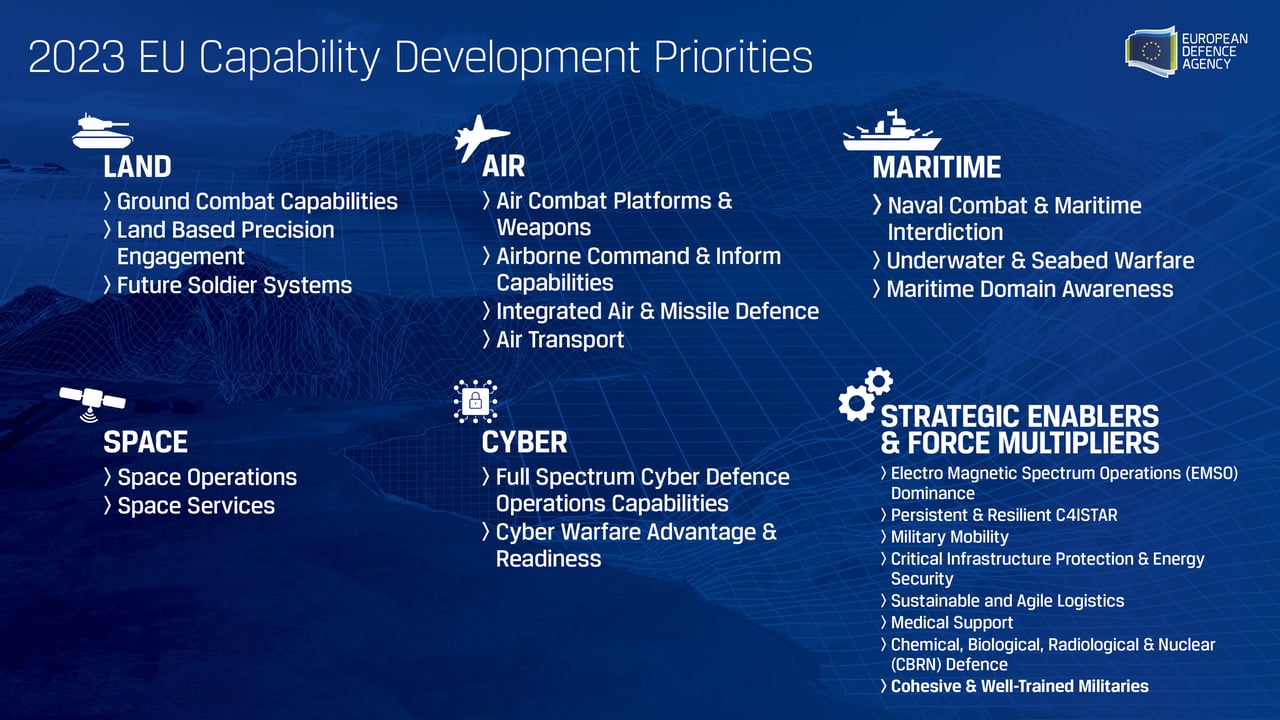

Which weapons systems are seen as a priority for Europe?

Europe is investing in multi-layered air and missile defence architectures because as Paweł Ksawery Zalewski, Polish secretary of state for national defence, said last year: “Having an advantage in the air defines the war".

For example, the European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI), launched in October 2022, seeks to create an all-encompassing defence system that integrates capabilities ranging from short-range to exoatmospheric levels.

In addition, drones, missiles, artillery, strategic enablers, military mobility, cyber capabilities, and artificial intelligence have been listed as priority areas. Namely, drones have become a crucial tool in the war in Ukraine, prompting both Kyiv and Moscow to quickly develop their own industry. And today, the main exporters of military drones are China and Turkey.

What challenges does the EU face in strengthening its military capabilities?

While increased defence investment is welcomed, the industry seeks long-term or multi-year procurement contracts for stability, sustained innovation, and tech development. The ‘built-to-order’ system typical of peacetime, which the EU defence industry is based on, has resulted in long waiting times for advanced defence capabilities.

Defence cooperation, including joint ventures and shared procurement, is growing, but it remains limited. There have been specific efforts to boost artillery ammunition production, an area where Ukraine has a high demand. But the EU’s pledge to deliver one million 155-mm-calibre artillery shells between March 2023 and 2024 was impossible to fulfil in time, showing the challenges ahead. The EU Commission estimated in 2022 that the lack of cooperation leads to annual costs ranging from €25bn to €100bn.

Another of the key issues for the EU’s defence industry is fragmentation, especially outside the aeronautics and missile sectors. Fragmentation not only triggers duplication and higher production costs but also interoperability problems, limiting its scale and operational effectiveness in the field. As an indication, EU member states have provided ten different types of howitzers to Ukraine, according to the Draghi report. In addition, the EU operates 12 different types of battle tanks, whereas the US manufactures just one (the M1 Abrams).

Meanwhile, external dependencies also factor in. Between 2007 and 2016, over 60 percent of Europe's defence procurement budget was spent on non-EU military imports, leading to third-country controls and restrictions on the equipment. A 'European preference' in defence procurement, pushed mainly by France, did not find consensus during informal talks of EU leaders in February – and given the need to scale up quickly, many countries are calling for a system to be as open as possible.

Do European countries have nuclear weapons?

As of January 2022, France had 290 warheads, with 98 delivery systems, including submarine missiles and air-launched missiles. The UK had 225 warheads, 120 operational, deployed on five submarines, with 105 in storage, according to the Arms Control Association.

Meanwhile, it is reported that Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey all host US nuclear weapons. Poland has recently called on Washington to deploy nuclear weapons in the country, admitting that having its own capacity would take decades.

Will the EU develop its own nuclear deterrent?

Germany’s chancellor-to-be Friedrich Merz is trying to court French president Emmanuel Macron and UK PM Keir Starmer to share nuclear weapons. “We have to be stronger together in nuclear deterrence,” Merz said earlier in March.

His remarks come after Macron floated the idea of extending the French “nuclear umbrella” to European countries. However, the debate is still in its early stages. While France's nuclear arsenal of around 290 warheads may be sufficient for national deterrence and some European partners, it is not enough for all of Europe.

Moreover, French defence minister Sébastien Lecornu recently said that the nuclear deterrent "is French and will remain French — from its conception to its production to its operation, under a decision of the president."